Book Revue: H.G Wells' War of the Worlds

A Prelude to the Future

Welcome to Book Revue! It's time to talk about Earth's most prolific writers, starting with one of the most recognizable pieces of literature in all of history. H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds (1898) is considered one of Earth's most significant war novels. Serving as the first autobiographical recounting of an extraterrestrial encounter, the novel was a masterpiece in storytelling and remains a window into humanity’s past. More than two billion copies have been published across over twenty planets and moons, a feat so prolific that even the Harmakhians regard it as a historical text. This literary miracle resulted from a life-threatening encounter that changed Earth as we know it, but to understand the weight behind the words within this text, we must meet the man behind the pen.

A line drawing of Wells' (1898)

The Man Behind the Pen

Throughout his

life, Hubert George Wells, born in 1866, wrote over fifty novels

focusing on the themes of science and the future of humanity. He is

considered the “father of scientific literature”, not because of a

profound understanding of the hard sciences but because of his unbridled

spirit of discovery. Initialy growing up in the British countryside, Wells was a teacher and an artist before he depicted to teaching his peers through the pedagogy of literature. Whether it was the stories of others or his recounting, Wells could expose the aspects of reality that were

stranger than fiction and show them to the rest of the world as a

reflection of life itself.

A photograph of Wells circe. 1921

The Early Years

Many of Wells’

novels were rooted in the critique of contemporary society. They found

answers to the unexplained phenomena hidden in all corners of the world

through “fantastic stories”. In his first work, The Time Machine (1895),

Wells recounted his experience with the enigmatic “Time Traveler.” The

novel was dismissed as fiction then but proved true when time travel’s

feasibility was confirmed nearly a century later, causing historians and

readers alike to revisit this novel. Wells’ first proper breakout hit

was in The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), a tale of a shipwrecked

sailor who ends up trapped on the island of a mad scientist who creates

human-animal hybrids. While the events of the book were debated as

fictional or non-fictional, the work was a hit and later considered a

proto-commentary on the treatment of EMOs (Essence-modified organisms).

Wells’ continued to be regarded as a talented fictional author even with

his third hit, The Invisible Man (1897), a story about a murderous

scientist who renders himself permanently invisible in a botched

experiment, selling two million copies within six months. All of this,

however, would change by year's end when the Vermilion Empire of Harmakhis

would descend from what was known as the Red Planet, Mars, at the time

and lay waste to the European countryside.

Famous author, Ray Bradbury, sits in a prototype time-sled as depicted in The Time Machine (circe. 1960)

War of the Worlds

To this day, scholars debate which of Wells’ novels were fiction or reality as the author insisted all of his works, save his essays, were “as real as the skin on my face”. War of the Worlds (1898), however, remains the only novel that most, if not all, readers take at face value due to the sheer realism depicted in the text. Wells’ describes his encounter with the “Martian” war machines and his attempts at self-preservation in the wake of the Vermilion Empire's brief takeover of Western Europe in the winter of 1897. After the Empire’s ground forces died to Earth-born illnesses and their presence on Earth disappeared, War of the Worlds was published months after news circulation of the events. Despite this, the novel revealed details never seen before and soon became regarded as a biographical recounting of the war. In the current day, the human supremacy and xenophobia displayed by Wells are seen as backward, but the work’s historical value cannot be denied as it is often viewed through that lens.

One of Henrique Alvim Corrêa’s Illustrations for The War of the Worlds depicting a Harmakhian

After the Fall

Beyond War of the Worlds, Wells pivoted from telling stories about Earth to stories about space and essays on futurist social criticism later in his career. In the wake of the War of the Vermilion Empire and humanity’s discovery of extraterrestrial life, Wells became an opponent of human supremacy, publishing The First Men in the Moon (1901) before the Astronomy Club’s trip to the moon a year later, which served as a preemptive critic of colonial efforts on Earth’s moon, and The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth (1904), a story that was described as “a fantasia on the change of scale in human affairs” and extrapolated on humanity’s advancements in Essence and biological sciences.

An illustration of a spacecraft from The First Men in the Moon (1901)

The Later Years

Throughout his career, Wells looked to tell the stories no one had heard before. Still, now that humanity’s eyes had turned towards the stars, he turned to change the minds of those who would be voyaging beyond Earth while still revealing the things about Earth that had yet to be undiscovered. During the first two World Wars, Wells coined the term “the war to end war” when writing The War That Will End War (1914), which discussed views of pacifism in the face of wartime. After the First World War, Wells became obsessed with Russia, taking multiple trips and eventually writing Russia in the Shadows (1921), claiming the nation as “the completest that has ever happened to any modern social [organization]”.

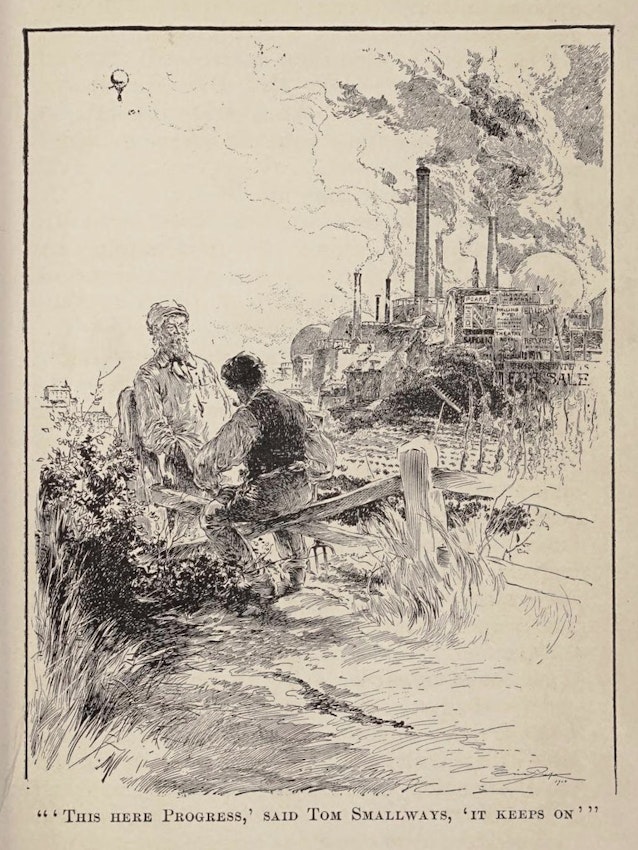

Illustration by Eric Pape from the first American edition of H. G. Wells’ The War in the Air (1908)

Legacy

Wells continued to critique Earth-centric politicians and cosmonauts, causing his fellow storytellers to view his pivot from fiction to non-fiction as crude. George Orwell called him “too sane to understand the modern world,” and G. K. Chesterton stated, "Mr. Wells is a born storyteller who has sold his birthright for a pot of message”. Two years before his death, Wells said his epitaph should be “I told you so. You damned fools”. His hypothetical epitaph would later be proved true by dropping the Golgotha Trifecta during World War II. This event eerily shadowed his earlier work, The World Set Free (1914), and once more proved Wells as a visionary, so much so that some believed he was the mysterious Time Traveler he wrote of in his first work. Even still, among all of his works, the trend of Wells’ search for a utopia remains, whether on Earth or in the stars. Wells’ works stay in the archives of databases across the Interstellar Republic and beyond, cementing him as a widely-renowned wordsmith and a man always reaching for the stars.

Comments

Post a Comment